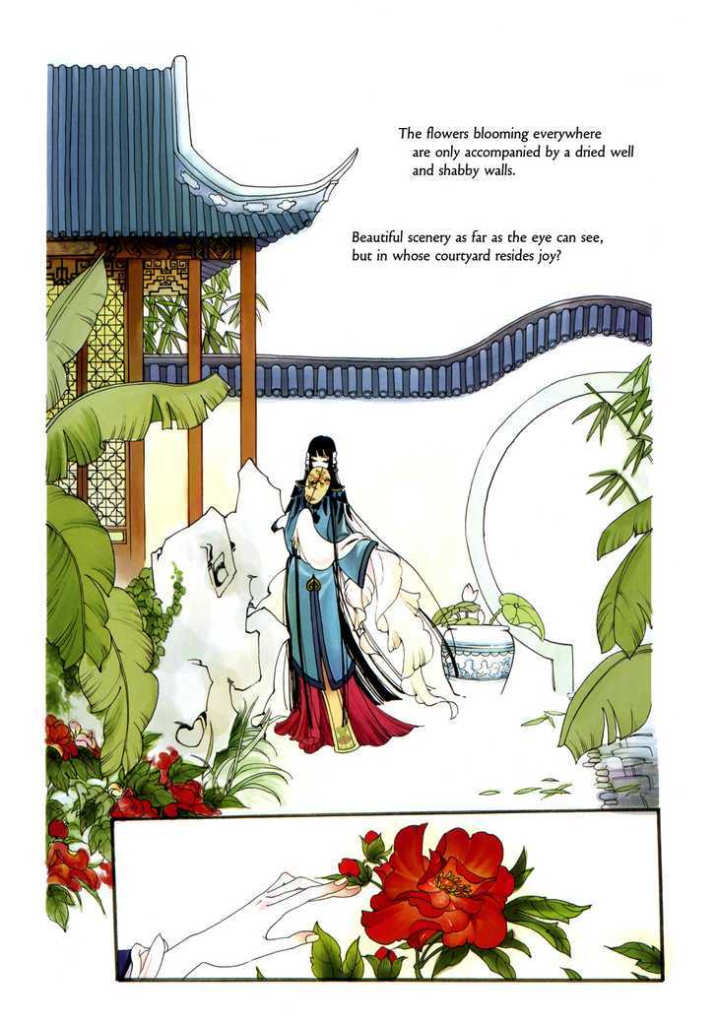

Artwork: Peony Pavilion, Chapter 1, by Xia Da

On the frontispiece of what the editor presents as the first volume offering a comprehensive account of tales of Chinese mythology in English, the volume Myths and Legends of China edited by E.T.C. Werner in 1922, one reads the quote:

But this Orient, this Asia, what, finally, are its real borders?… These borders are of a clarity that allows no error. Asia is where vulgarity ends, dignity is born, and intellectual elegance begins. And the Orient is where the overflowing sources of poetry are. (Mardrus, The Queen of Sheba, cited in Werner 1922: 12)

Yet, negative prejudices on Asian culture regrettably always existed and continue to exist. Did Tolkien share such a despicable attitude? Commenting on the identification of the East with evil through the location of Mordor in the South-East in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien stated: “The goodness of the West and the badness of the East has no modern reference. The concept came about through the necessities of narrative” (Scull and Hammond 2006 C: 640). Tolkien also commented on the identification of North with goodness: “Auden has asserted that for me ‘the North is a sacred direction’. That is not true. [. . .] That is untrue for my story, a mere reading of the synopses should show. The North was the seat of the fortresses of the Devil [ie. Morgoth]” (Letters 376, no. 294).

From Kittredge’s Study of Gawain and the Green Knight, cited as a reference in Tolkien and Gordon’s 1925 edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, one gathers that Tolkien knew the contributions by Reinhold Köhler to the second volume of Orient und Occident (Kittredge 1916: 196 n. 7; 206 n. 2; 207 n. 2; 208 n. 2) and Felix Liebrecht’s contribution to the second volume of Orient und Occident (Kittredge 1916: 267 n. 1).

Commenting on word order in English, Tolkien made a passing comment on Chinese:

‘Helms too they chose’ is archaic. Some (wrongly) class it as an ‘inversion’, since normal order is ‘They also chose helmets’ or ‘they chose helmets too’. (Real mod. E. ‘They also picked out some helmets and round shields’.) But this is not normal order, and if mod. E. has lost the trick of putting a word desired to emphasize (for pictorial, emotional or logical reasons) into prominent first place, without addition of a lot of little ‘empty’ words (as the Chinese say), so much the worse for it. (Letters 226, no. 171)

When consulting Clouston’s book of analogues of Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale, Tolkien remarked: “I cannot myself read the Oriental languages required for a first-hand investigator: Pali, nor Persian nor Arabic nor Chinese, to name the most important” (Bowers 2019: 259). Volume 19 of the Cabinet des Fées, dedicated to “Les contes chinois, ou Les aventures merveilleuses du mandarin Fum-Hoam” [The Chinese Tales, or The Marvellous Adventures of the Mandarin Fum-Hoam], was read by Tolkien according to Cilli (TL 188).

Tolkien might have also read the 1921 The Chinese Fairy Book, edited by Richard Wilhelm and translated by Frederick H. Martens, where he would have found the tale of “The Lady of the Moon”:

In the days of the Emperor Yau lived a prince by the name of Hou I, who was a mighty hero and a good archer. Once ten suns rose together in the sky, and shone so brightly and burned so fiercely that the people on earth could not endure them. So the Emperor ordered Hou I to shoot at them. And Hou I shot nine of them down from the sky. Besides his bow, Hou I also had a horse which ran so swiftly that even the wind could not catch up with it. He mounted it to go a-hunting, and the horse ran away and could not be stopped. So Hou I came to Kunlun Mountain and met the Queen-Mother of the Jasper Sea. And she gave him the herb of immortality. He took it home with him and hid it in his room. But his wife who was named Tschang O, once ate some of it on the sly when he was not at home, and she immediately floated up to the clouds. When she reached the moon, she ran into the castle there, and has lived there ever since as the Lady of the Moon. (Wilhelm 1921: 53)

The peculiar idea of the theft of immortality, while absent from Tolkien’s Legendarium, would surely have interested Tolkien, because of his passion for tales concerning mortality and immortality. The man Hou I shooting nine suns down could also have to do with Melkor’s destruction of the Two Lamps in the early days of Arda as well as with his killing the Two Trees and his subsequent attempt at ravishing the Sun Maiden Arien in Tolkien’s Legendarium. Moreover, the Chinese tale continues with a visit of Chinese courtiers to the Moon, where they meet the Lady of the Moon and a man in the moon, which reminds one of the song “The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late” in The Lord of the Rings. Thomas Honegger proved how Tolkien was aware of the myths concerning the Man in the Moon (Honegger 2005), and so he may well know the Chinese version too.

Tolkien may also have been interested in the Four Great Classical Dramas of China: Romance of the Western Chamber, The Peony Pavilion, The Palace of Eternal Life, and The Peach Blossom Fan.

Romance of the Western Chamber is a drama in twenty-one acts in five parts written by Wang Shifu in the 13th-early 14th century. It tells a story remarkably similar to Tolkien’s with Edith: a young couple, the promising scholar Zhang Sheng and the noble maiden Cui Yingying, is divided by the opposition of her mother, but overcomes the obstacle and manages to get married thanks to the help of his friend General Du, who fulfills the task required to get her hand in his behalf; the assistance of her maid Hongniang, who arranges a private meeting for the couple; and due to the abnegation of Zhang Sheng in his studies, which earns him the respected social position which her mother further requested in order for him to marry her. The play was first translated in English in 1937, and does not contain fantastic elements, so probably it cannot have been an inspiration for the story of Beren and Lúthien, but Tolkien might have liked it if he knew it.

The 17th century plays The Palace of Eternal Life and The Peach Blossom Fan are of lesser interest to Tolkien, being the former a romantic play telling the love story between an emperor and his concubine on earth and in the afterlife, and the latter an historical drama about a couple divided by war who are never reunited because they realize that history subdues love.

However, in the 16th century The Peony Pavilion, written by Tang Xianzu, one finds an act called “Infernal Judgement,” where the heroine Du Liniang appears before the Judge of the Dead in the afterlife to plead for her own return on Earth to be united with her dream lover Liu Mengmei, and they end up together to get married and live happily ever after. The first full Western translation was made by Vincenz Hundhausen in German in 1937, but an introduction to the play with selected excerpts translated into German was published in 1929 by Hsu Dau-lin in the journal Sinica, so it is conceivable that Tolkien’s new focus on Lúthien’s song before Mandos pleading for Beren to return to life in the 1930s “Sketch of the Mythology” and “Quenta Silmarillion” might be indebted to The Peony Pavilion and not only to Sir Orfeo. In the context of the belief in reincarnation, after all, Beren’s return from the dead would be way less exceptional.

The first complete English translation of The Peony Pavilion, by Cyril Birch, would not be published until 1980, but a scene from the play was published by Harold Acton in 1939 in the journal T’ien Hsia Monthly. Harold Acton was an English Catholic born in Florence from a family of baronets who studied at Eton College and Oxford and lived in China from 1932 to 1939. His 1941 novel Peonies and Ponies tells the story of an English espatriate in Beijing and significantly refers to The Peony Pavilion both in its title and in having the protagonist Philip Flower dream of a Chinese lady that he falls in love with, Tu Yi. Tolkien would have probably at least heard about Acton, and if he was curious to learn more, he might have learned about The Peony Pavilion from his translated excerpt, and consulted the German translation by Hundhausen. In this case, the influence on the tale of Beren and Lúthien could only account for the later changes to the tale from 1940 until Tolkien’s death in 1973.

Du Liniang’s (Bridal Du in the translation by Cyril Birch) plead to the Judge of the Dead is indeed delicate and tender, as she tells him how she died awakening from a dream of love in a pavilion of flowers:

BRIDAL DU: If I have any youthful freshness it is because I was born this way, and I have neither married nor drunk wine. But I am here because I once dreamed of a young scholar, beneath the apricot trees in the garden behind the Prefect’s residence at Nan’an. He broke off a willow sprig and asked for a poem on the subject. He was affectionate and gentle and we loved each other dearly. On waking from the dream I fell to musing, and composed the lines,

Union in some year to come

with the ”courtier of the moon”

will be beneath the branches

either of willow or apricot.

Then, falling into longings, I lost my life

(Tang 2002: 129)

The name Liu Mengmei in fact means “Willow Dream of Apricot” (Tang 2002: 134 n. 31). In Xu Yuanchong and Ming Xu’s translation, the lines that Du Liniang composed and recites are: “If the Moon Goddess be a bride, / She would stand by the willow’s side” (Tang 2013: 139). The Judge asks the flower spirit (or flower fairy) of that garden whether it is possible to die of dreaming or of flowers, and the spirit replies in the affirmative. Du Liniang then asks:

BRIDAL: If Your Honor graciously pleases: Is it possible to investigate the source of these distressful feelings of mine?

JUDGE: The matter is all noted in the Register of Heartbreaks.

BRIDAL: Then might I trouble you to determine whether my husband was to have the name of Liu or Mei, Willow or Apricot?

JUDGE: Let me see the Register of Marriages. (He turns away from the defendant to examine it) Here it is. Here is a Liu Mengmei, Prize Candidate in the next examinations. Wife, Bridal Du, loved in the shades, later formally wedded in the world of light. Rendezvous, the Red Apricot Convent. Not to be divulged. (He turns again to face the defendant) There is a person here with whom you share a marriage affinity. On this account I shall release you now from this City of the Wrongfully Dead, so that you may wander windborne in search of this man.

(Tang 2002: 133)

The contrast between Du Liniang’s sweetness and the Judge’s stern countenance is based on the same presuppositions as Lúthien’s encounter with Mandos.

In his preface to The Peony Pavilion, Tang Xianzu himself refers to his sources, to be found in the old tales of Li Zhongwen and Feng Xiaojiang included in Taiping guangji, the Song dynasty collection of 7021 tales that was first completed in 971 CE and, after being forgotten, had been recovered in Tang’s youth. The version by Li Zhongwen lacks an explanation for the girl’s return to life and is tragic, since she dies again after being resurrected because of the skepticism of the lovers’s parents. However, Feng Xiaojiang’s version offers a supernatural explanation and it has the happy ending. Wilt L. Idema translated it as follows:

The prefect of Guangping, Feng Xiaojiang had a son called Mazi. Mazi dreamt of a girl of about eighteen or nineteen, who told him that she was the daughter of the preceding prefect Xu Xuanfang. She said that she had unfortunately died before her time and had been dead for four years, but that, as she had been wrongly killed by demons and according to the registers of life was destined to reach an age of over eighty, she had now been allowed to return to life to become his wife – would he marry her? When Mazi dug up her coffin and opened it, she had already come back to life. Thereupon they became husband and wife. (Idema 2003: 118)

Another source has proven to be the 1541 anonymous short story Du Liniang muse huanhun [Du Liniang Craves Sex and Returns to Life], where also the “Infernal Judgement” scene is lacking, but it has the happy ending and, when the phantom of Du Liniang appears to Liu Mengmei and he accepts her as his lover, after they share their bed of passion, she asks him to unbury her body since she returned to life because “you and I have an unfinished karmic bond of marriage from a previous existence” (Idema 2003: 141). This notion is especially interesting when connected to Tolkien, since it suggests the idea that Beren and Lúthien may have been husband and wife from the start in the mind of Eru Ilúvatar. There is no indication that Tolkien might have known Tang Xianzu’s sources, even if he knew his play, and any hypothesis of influence in this sense is not proven, but at the very least The Peony Pavilion and its sources in Feng Xiaojiang’s tale and the anonymous Du Liniang muse huanhun constitute an interesting analogue.

Works Cited

Acton, Harold. 1983. Peonies and Ponies: A Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. 1st edition 1941.

Acton, Harold. 1939. “Ch‘un-hsiang Nao Hsueh.” T’ien Hsia Monthly, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 357–372.

Bowers, John. 2019. Tolkien’s Lost Chaucer. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Cilli, Oronzo. 2019. Tolkien’s Library: An Annotated Checklist. Edinburgh, LunaPress.

Honegger, Thomas. 2005. “The Man in the Moon: Structural Depth in Tolkien.” Root and Branch: Approaches Toward Understanding Tolkien. Zurich and Jena, Walking Tree Publishers, pp. 9–58.

Hsiung, Shih I, translator. 1935. The Romance of the Western Chamber. London, Methuen.

Hsu, Dau-lin. 1929. “Die chinesische Liebe.” Sinica. Zeitschrift für Chinakunde und Chinaforschung, Vols. 4/6, pp. 241–51.

Idema, Wilt L. 2003. ““What Eyes May Light upon My Sleeping Form?”: Tang Xianzu’s Transformation of His Sources, with a Translation of “Du Liniang Craves Sex and Returns to Life”.” Asia Major, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 111-145.

Kittredge, George Lyman. 1916. A Study of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Scull, Christina, and Wayne G. Hammond. 2006. The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. 2 Vols. London, Harper Collins.

Tang, Xianzu. 2013. Dream in Peony Pavilion (Chinese-English). Translated by Xu Yuanchong and Ming Xu. Beijing: Dolphin Books.

Tang, Xianzu. 2002. The Peony Pavilion. Translated by Cyril Birch. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 1st edition 1980.

Tang, Xianzu. 1937. Die Rückkehr der Seele. Ein romantisches Drama. Translated by Vincenz Hundhausen. Zürich and Leipzig, Rascher Verlag.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. 2016. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter. London, Harper Collins.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel and Eric Valentine Gordon, editors. 1925. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Werner, E.T.C., editor. 1922. Myths and Legends of China. London: George T. Harrap & Co., Ltd.

Wilhelm, Richard, editor. 1921. The Chinese Fairy Book. Translated by Frederick H. Martens. Illustrated by George H. Wood. New York, Frederick A. Stokes Co.